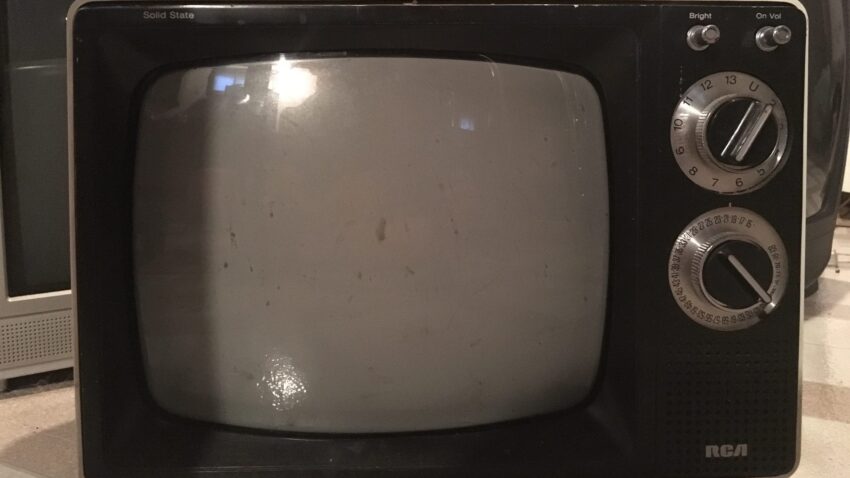

Those old analog TV’s that some of us remember from our childhoods (and that others have only seen on retro TV shows) didn’t just bring in our favorite shows, they accidentally taught us a lesson about the TV spectrum.

Many of them had separate knobs and antenna inputs for VHF and UHF, sending home the message that there is a frequency gap between channel 13 and 14. Smaller portable TV’s actually had three bands because VHF was split into the low and high bands.

Digital TV’s make these frequency gaps invisible. Not only is there no way of noticing the spaces between channels 6 and 7 and channels 13 and 14 on a modern TV, most of the stations show up as virtual channels that don’t match the actual RF channel on which the broadcast originates.

(To find out what channel a station actually transmits on, check this site’s TV market listings or search a site like RabbitEars.info or FCCData.org.)

The three bands have different characteristics, and are also different for digital broadcasting than they were for analog. So, here’s an explanation of the three TV bands.

VHF Low is RF channels 2 through 6 (54 to 88 MHz).

The first TV stations to sign on were on VHF Low. Analog stations in this band were allowed to use up to 100kW. (There was originally a channel 1, too, but it was quickly discontinued. And there’s a small frequency gap between channels 4 and 5, which allowed analog stations on both channels in the same city.)

In many cases, people with large rooftop antennas could reliably receive analog VHF Low stations at distances of 100 miles away. These distant signals provided the first TV service for many rural areas, and in some cases, the only TV service for many decades.

However, indoor reception of analog VHF Low stations was a lot more difficult. Even people living only a few miles away from transmitters sometimes had trouble receiving a clear signal using rabbit ears.

VHF Low frequencies are highly susceptible to interference not just from modern electronics but from power tools and vacuum cleaners. The frequencies are also susceptible to long-distance e-skip reception during the summer, which is fun for hobbyists but annoying for rural viewers who just want to watch their favorite shows.

With these issues known, most TV stations that had broadcast on VHF Low during the analog era chose to relocate to UHF or VHF High during the digital transition. Stations transmitting digitally on VHF Low are very difficult to receive with indoor antennas and may suffer interference even with a rooftop antenna.

(VHF Low is right below the FM band, meaning analog channel 6 audio transmitting on 87.75 MHz could be heard on FM radios. Some digital low-power TV stations still have special temporary authority to broadcast an analog audio carrier on that frequency.)

During the spectrum auction, a few stations (all outside the Upper Midwest) took buyouts to accept the downgrade of moving to VHF Low. The FCC acknowledged that VHF Low is the least desirable place for digital TV by offering higher payments to move to VHF Low than to VHF High.

VHF High is RF channels 7 through 13 (174 to 216 MHz).

During the early years of the analog era, these channels may have been seen as slightly less desirable than VHF Low channels because they did not have quite as large of a regional reach. They also came with a higher power bill because a 316kW analog signal was needed to come close to the reach of a 100kW signal on VHF Low.

However, VHF High proved to have one major advantage: it was a lot easier to receive with indoor antennas.

When the digital transition was completed in 2009, many stations that had transmitted in analog on VHF High chose to covert their existing channels to digital broadcasting rather than construct a new full-power UHF plant. Numerous TV stations have subsequently received reception complaints from many viewers, prompting many to seek moves to UHF.

UHF is channels 14 through 36 (470 to 608 MHz).

The UHF band used to go all the way up to channel 83, but channels 38 to 83 have been reallocated to cellular and other services in three separate auctions since then 1980s. Channel 37 (608 to 614 MHz) has always been reserved for radio astronomy.

To say that UHF struggled during the analog era would be putting it mildly. Many early UHF stations folded in the face of competition with VHF stations. Most TV’s needed a converter to even receive UHF stations until Congress passed the All-Channel Receiver Act in 1962.

The power bills were high, too, since a 5,000kW analog UHF signal was needed to (almost) replicate the coverage of a VHF signal. Only a few UHF stations in major cities could afford to transmit at the maximum power.

Ghosting was also a major problem for analog UHF stations. It’s literally what it sounds like: you’d see multiple images, or ghosts, due to the signal taking multiple paths to reach your TV as it bounces off of objects. Buildings, trucks, trees swaying in the wind, even people walking across the living room.

What used to be called ghosting is actually multipath reception, and it still exists. However, instead of ghosts, you get signal breakup.

Despite the multipath issue, UHF has proven to be the far superior place for digital TV broadcasting because the signals are the easiest to receive with indoor antennas; their narrower bandwidths are more suitable to smaller antennas.

Cable TV frequencies are different.

In the analog era, cable channels 2 through 13 used the same frequencies as broadcast channels 2 through 13. However, cable channels 14 and up are on different frequencies than broadcast UHF.

The earliest cable systems only used channels 2 through 13 and could be hooked right up to a TV for reception. Converter boxes became necessary once cable channels 14 and up launched (though they were originally called A, B, C, etc.)

In the 1980s, people who didn’t have a cable-ready TV and didn’t want to pay the rental fee for extra converter boxes could buy a “block converter” that would convert the cable frequencies to standard UHF channels, but the picture got fuzzier as the channels got higher.

In the digital world, cable channel numbers that display on a converter box have little meaning. Like virtual channels on broadcast TV, a cable channel on a converter box can originate on any frequency. The information is invisible to the cable user because only the cable company knows how its boxes are programmed.

Do you have a question about broadcasting? Email jonellis@northpine.com and I’ll do my best to find an answer!